Going back to my own story, the first six weeks with my colostomy were a nightmare. I ended up in rehab thanks to complications from surgery. While in rehab, I ended up back in the hospital with a pleural effusion. Two weeks after leaving the hospital, I landed back in the hospital to have a liver abscess drained. Through that entire time, it didn’t matter who changed my ostomy bag, I had leaks and bag explosions often. My mom was the one who learned to change the bag, and whether it was her who changed the bag or one of the nurses, I had leaks constantly. That was until my hospital stay to drain my liver abscess. The hospital’s ostomy nurse suggested a different bag to try, along with an ostomy bag. After that, leaks were a thing of the past and I was getting several days out of each bag change. After that, life got a lot better. I got through chemo with a colostomy bag. Eventually, I learned to change the bag with help, and then finally on my own.

Then I had a check in with my surgeon and suddenly I had a decision to make. By that point, my diagnosis of Lynch Syndrome had been confirmed. I knew I was at high risk of a second, unrelated colon cancer within the next ten years. I would need a colonoscopy every year for the rest of my life. During the discussion with my surgeon, I learned I was not a candidate for a “j-pouch.” A j-pouch is an internal pouch made surgically that connects the end of the small intestine to the rectum so that an ostomy bag isn’t needed. I wasn’t an candidate because of the size and placement of my original tumor. If I opted to remove my colon, I would have a permanent ileostomy. He also warned me that likely wouldn’t be happy with a straight reconnection of my colon. My tumor had been quite large (softball size) and close enough to my rectum that I would likely spend far more time in the bathroom than I wanted. I had several months to make my decision. With several months to think and pray about it, I ultimately concluded that it was in my best interest to remove the rest of my colon (along with other body parts, but that’s a topic for another post).

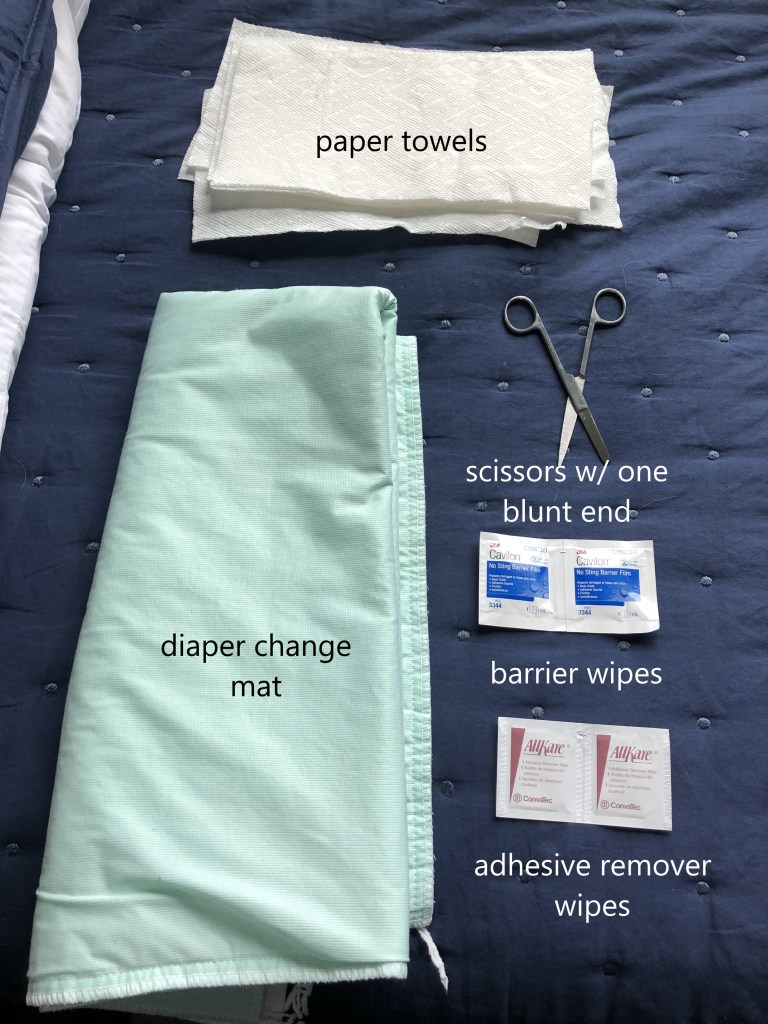

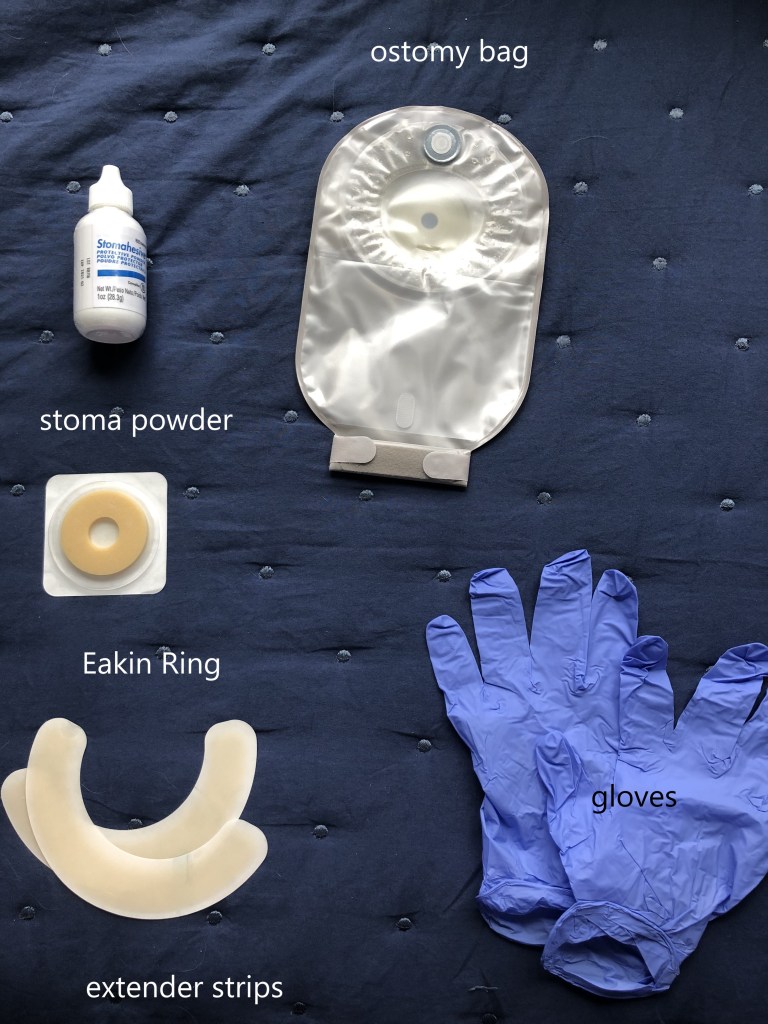

The first six to eight weeks after my ileostomy surgery were somewhat difficult. The difference this time was that I expected it. I was also used to changing the bag and leaks didn’t phase me. As it turns out, I had a leak just last night. Leaks now are annoying, but not the end of the world. I had expected to need a different type of bag than my colostomy bag, but as it turned out, the best bag system for my ileostomy was the same one I had used for my colostomy. When I had a colostomy, I only had to change my bag once a week. Now that I have an ileostomy, I have to change it every four days. This is largely a result of the consistency of the stool. Since it is more liquid, it is better able to get under the seal of the bag. Stool is very acidic on skin and keeping the skin around the stoma healthy is paramount. Broken skin is very painful and can keep the bag from sticking. Below I’ve included the things I use to change my bag.

In general terms, I first cut the hole in the new bag using a template from earlier changes. After putting on gloves, I use the adhesive remover wipes to remove the pouching system itself and any adhesive that is left behind. Without the remover wipes (or some other type of adhesive remover), you can easily damage the skin. Also, any adhesive left behind can keep you from getting a good seal and can lead to leaks. I make sure I use either a wet wash cloth or a wet paper towel to clean around my stoma. I don’t want any adhesive or adhesive remover left behind. I then change my gloves. I use two pairs of gloves so I don’t get stool on my skin under the new bag. I then use the stoma powder just around my stoma and then use the barrier wipes to get that powder wet. I do it again in a process called “crusting.” It both allows the skin underneath to heal and protect it from further breakdown. Next, I take out the Eakin ring and mold it to the shape of my stoma. It’s very sticky and easily moldable. Finally, I put on the new bag. On those days when I want extra confidence in my bag, I will use the extender stips around the bag. I don’t find them absolutely necessary, but they do give me the confidence that I have the new bag secure. I change my bag while laying on what amounts to a diaper change pad. I learned to change it lying down due to problems with my leg after my first surgery. I only have to wait 12-24 hours before getting it wet to allow the adhesive to fully adhere. I do it laying on the pad because the pad is easily washable if my ileostomy spurts while I’m changing it. I learned early on that eating a couple marshmallows about 30 minutes before the change can stop up my system long enough to change the bag. An ostomy has a mind of its own, but marshmallows for me help nudge it to my whims.These days, nearly 2 years after my colostomy, it only takes about 15 minutes to change it, and then I don’t have to worry about it for another four days. It’s now simply part of my routine.